Can You Hear Me Now? Standing Out in the Crowd.

Most companies spend their entire marketing budget convincing us their products are unlike any others available. The makers of Tide, a product not too different from Gain or Members Mark Ultimate Clean Liquid Laundry Detergent, only want you to think two things: “Tide cleans clothes” and “Tide cleans clothes better and differently than anything else.”

Parity products are the ones that are relatively the same from brand to brand, such as laundry detergent, or the ones that have been regulated to the point that each brand is required to offer relatively identical services.

You’re likely someone (or you work for someone) who offers a parity product or service. You’re struggling to stand out from the crowd. It’s OK. This is the world in which most of us work.

Doctors, lawyers, bankers, and yes, even marketers all say they can do something better than someone around the corner.

Do you know Paul Marcarelli? You likely recognize him as the “Can you hear me now?” guy. He was Verizon’s longtime pitchman before being picked up by Sprint. He (sometimes annoyingly) drove home the differentiating factor of cellular service.

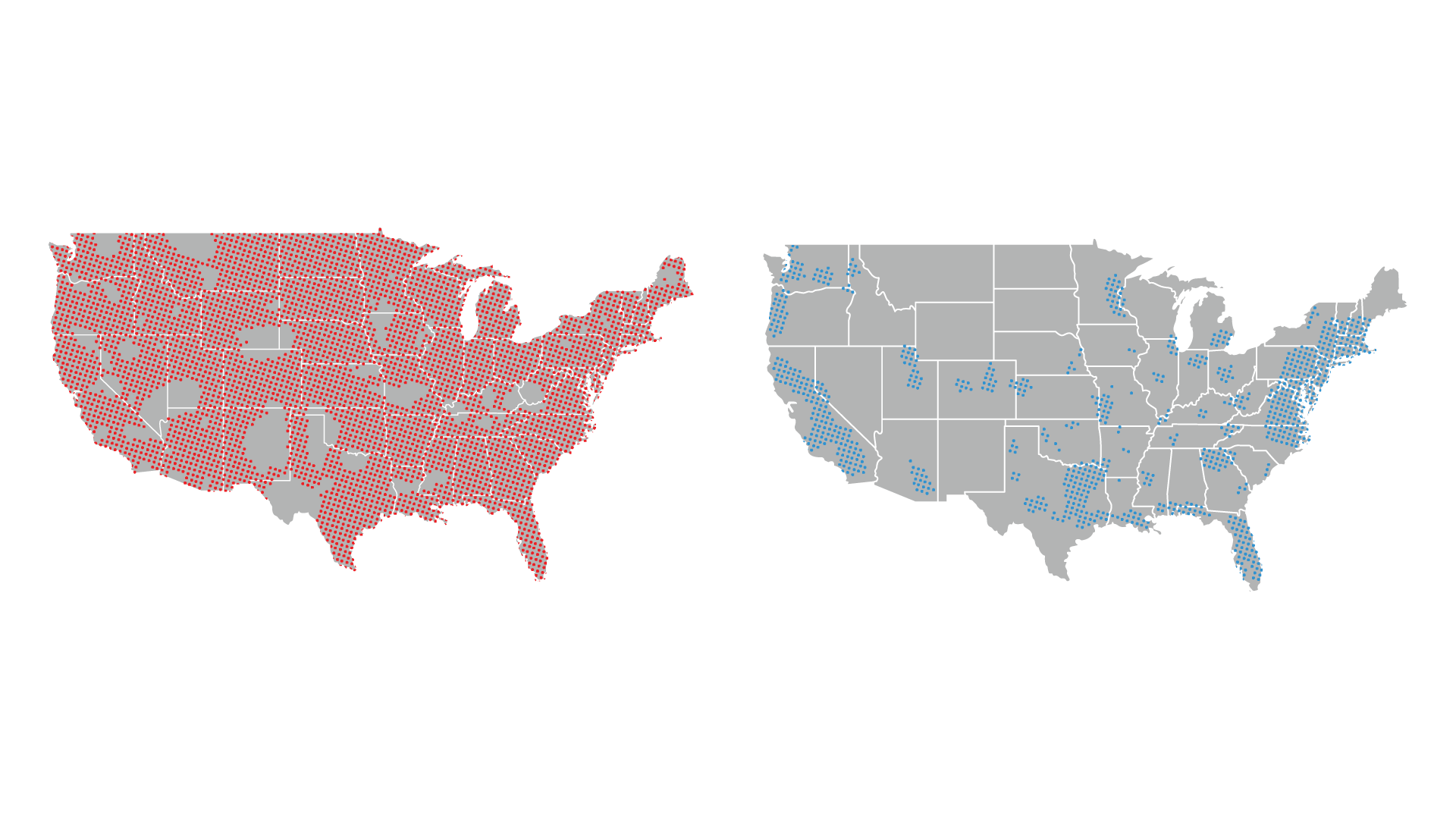

Cellular service is something that isn’t quite a parity product. When each cellular company offered a free thingamajig that did roughly the same thing, there was separation provided by the coverage map. One might have asked, “Where does that thingamajig work?” That used to make all the difference in the world.

But that was the past. As the cellular industry has matured, one provider’s coverage map has become much too similar to the maps of others. Since the iPhone gained wide release, there are few (or no) compelling, exclusive devices.

Now we’re talking about call quality, which is so similar between providers that few people care. Even worse, the once-exclusive service is now in the past, and it began bundling with other services such as TV and home Internet—just to capture a bit more profit.

Basically, cellular service is in the “anti-disruption model.” Instead of innovating, it’s delving deeper into the old “tried and true.”

But service delivery and product differentiation aren’t the only ways to disrupt. It is possible to reframe a message well enough to stand out. Sprint recently made a bold move to level the playing field. Sprint is taking an active role in turning cell coverage into a parity product.

Most companies don’t want their products to be considered parity products. Tell bankers their bank offers the same products as another bank and they will disagree on the grounds of having more qualified lenders or more personable staff. Most of their claims will be about subjective differences, which is how parity companies differentiate themselves.

The financial sector is so highly regulated that I’m not allowed to make definitive claims with financial clients. I can’t say I have “a better bank” that is “guaranteed to save you money.” Yet I’m also required to be very specific, so any ambiguity requires extensive footnotes, which tends to kill the emotion of an advertisement. The same thing goes for the medical field.

Advertising in parity markets is totally possible, but it requires a great deal of thought. I can call a soda the best-tasting soda on the shelf because it’s a subjective claim in a relatively unregulated market. Even if a doctor has the highest patient ratings and the most certifications in a region, I can’t call her the best doctor in the region.

Banks can’t claim to be “the best bank in town,” but they can claim to be “the bank where everyone knows your name” or “the hometown bank” or even “the small town bank with big bank services.”

Sprint’s network has been improving at a faster pace for the past five or so years, but it still hasn’t outpaced Verizon.

Ostensibly tired of being on top-five lists without ever being the top network, Sprint stopped settling for being only one of the best and lumped all the major networks into the same basket.

Back to Paul Marcarelli. After a hiatus from advertising, he popped back on the scene pitching for Sprint.

There’s a separate lesson here in paying someone for brand equity, then letting him leave. Imagine if Colonel Sanders told you to try Popeye’s Chicken.

Now, Marcarelli begins Sprint commercials by saying, “It’s 2016 and every network is great. In fact, Sprint’s reliability is now within 1% of Verizon….”

Sprint is obviously tired of jostling for business with the rest of the pack.

Instead of continually claiming to be one of the best networks, but not quite the best, Sprint decided to level the playing field by turning cell coverage into a parity product. It’s making the claim that every network worth its salt is so good that you, the common consumer, probably won’t notice a difference.

Marcarelli makes the argument that all the major cell networks are offering pretty much the same coverage with different packaging. Then he adds, “and Sprint saves you 50% over Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile’s rates.”

He’s asking if a 50% higher bill is worth it for less than 1% better coverage.

Sprint is turning parity marketing on its head. It’s no longer claiming to be the best or nicest or easiest to work with. It isn’t the network that knows you and your family better than the others.

Sprint is basically saying, “Hey, we’re about as good as it gets, and we’re a whole lot less expensive.”

It’s calling the other networks out on price by asking, “How can you justify those prices without really being any better?”

As business owners, it’s difficult to swallow our pride enough to take this approach, and I applaud Sprint for choosing honesty and practicality over pride. It could easily tout its network size or its different deals, but then it would be running the same campaign as the other companies—companies that offer only slightly better service.

When I work with business owners who are trying to sell themselves as the cheapest and the best, I tell them to choose one aspect because no one will believe both. How can you be better and cheaper than your competitors? I tell them to act like they’re the best or to lower their prices to be the cheapest.

The next time Verizon says, “We’re America’s best network,” Sprint can say, “Yeah, but how much better? Are you really $40 a month better?”

Sprint gets it. It isn’t the best, but it’s damn close, and it’s the cheapest.