The data is there, but you can’t get your arms around it.

Oh, data. You are so big. So bright. So beautiful. But like a perfectly curated Instagram post that is filtered to perfection, you often feel unattainable.

As with content, starting to develop a strategic approach to data mining, transformation, and analysis requires support across the organization and commitment to the activity over the long run. Also as with content, there are ways to earn “quick wins” — in this case, connecting a few systems as you expand your data aggregation to include more and more information over time.

Demographic data is often the first step. Ensuring you have an accurate understanding of the basic traits of your customers is baseline. This often comes from your core system, but can also be augmented by other platforms like online/mobile banking and rewards or loyalty platforms. Behavioral data is the hardest to build, but the most powerful by far. This data comes to life by combining email automation systems, website analytics, social media metrics, mobile and online banking behaviors, and transactional data.

The key? Start small. One system connected to another. One focused insight tested.

Discover who has used your mobile app in the past 45 days. Those are your true mobile customers. Determine the top three channels customers use (or doesn’t use) and inform them of alternatives. Uncover a customer’s best email by assigning a scoring system based on engagement with their multiple emails that often live across different systems within your bank.

It’s a long road. A commitment. But the insights you glean will inform your marketing, product decisions, and investments in customer experience for years to come.

Intimidated by all that data? Work with an agency that has experience marrying multiple data streams into one actionable strategy.

Marketing a bank is harder than ever. New techniques and technologies abound. The never-ending cycles of approvals to adopt change are extended as IT and compliance departments balance advancement against risk. On top of that, most banks are actually performing pretty well—which sounds great…until you’re challenged to do better next year.

As banks realize the need to grow in marketing sophistication, many are reaching out to agencies for the first time. I want to help you find one—and it doesn’t even have to be mine.

Now, let’s address the elephant in the room: “But you own an ad agency!” I sure do. But I’ve learned a big lesson over the years in this business: good relationships are worth their weight in gold. I’ve learned a few other things in that time, and I want to share some of them with you.

It’s really not about hiring the best agency, but the best fit. It would be a tragedy to hire an agency with terrible creative talents, but it’s worse (by many orders of magnitude) to hire an agency that’s a bad fit.

This is why you can trust my advice as an agency owner. Even if I spent the rest of this article trying to subliminally convince you that we’re the best bank marketing firm out there (even though we are), I couldn’t determine if we are a fit. And I’m much more concerned with fit. You should be, too. Trust me.

So how do you find the best fit for your bank?

Mabus Agency President Josh Mabus discusses the keys to hiring the right agency with some of the creatives on our staff.

Read or listen to Josh’s full article, “So You’re Thinking About Hiring and Agency,” here.

Subscribe to the Bank Marketing Blogcast and never miss an episode.

I feel the need to voice this concern about the financial industry. Maybe I shouldn’t—I actually think it’s a recipe for success and I certainly don’t want to give the competition too much fuel.

But, I genuinely feel you’ll read this, be inspired, and take no action.

You’ll agree, but you won’t change. You’ll like what I have to say, but not take on the fearless attitude required to cut through varying degrees of bureaucracy, organizational politics, and technological sludge. Forgive my cynicism, but remember, I’ve worked in the banking industry for some time now.

The Current State of Data in Financial Institutions

There are good conversations taking place between financial marketing teams, IT departments, and bank C-suite execs across the country, conversations about the “multi-channel” retail world in which we live, the need to improve the “branch experience,” and preparing companies to “go mobile.” These discussions center around implementing new customer-facing technologies, evolving the role of a branch banker, and exploring back office automation tools that signal the greatest leap in financial experience since the arrival of online banking in the mid-90s.

Yet, good conversations on how to better use data remain elusive. Banks have pursued “better reporting” since computers replaced paper ledgers decades ago, and reporting is better, too. It just hasn’t evolved. We still rely on classic metrics about our customers to determine their value and potential. Reports like “Top 25 clients by deposit dollars” or “Customers who have online banking” continue to define the furthest reaches of accessible customer intelligence at small- and mid-sized banks.

There has been little buy-in for new metrics from those at the top of financial companies, and plenty of pushback on just how much data and customer intelligence can actually inform marketing, selling, and service decisions.

The current modus operandi? In most banks with less than $10 billion in assets, data is delivered as:

- PowerPoint presentations, PDFs, or Excel worksheets from a vendor you hired

- MCIF export files

- IT reports

- An analyst’s combination of three to four spreadsheets

This information often satisfies a single reporting need by answering isolated questions like these:

- How did we do on deposit growth in this market over the past six months?

- What does loan growth look like in Region X?

- How many CDs are 45 days from maturity?

Then, there are the occasional deep-dives, which include questions like these:

- How many active mobile banking users do we have?

- How many of our customers bank elsewhere?

- Who are our most profitable customers? (Cue the cringing.)

- How many products do we sell in the first 90 days of a new relationship?

These are the questions that, frankly, lead to a type of reporting that’s often misguided and simply incorrect thanks to disparate systems, incomplete vendor service, and poor aggregation practices.

Don’t Agree? Try This Experiment.

Determine one report you need, like a three- or six-month trend report. Next, request this report from your IT department or from the technology or product vendor where your data is housed. Then, if possible, request the same data from another source within the bank. Also, have a vendor use the same data to pull down the numbers for you. Try to get the info yourself if possible.

Compare notes. On the standard reports (DDA growth, loan growth, CD maturities), everything might be close. If it’s not, you have much more work ahead of you. On a deep-dive report, I imagine you’re going to see some variation—maybe a lot of variation.

How Can Financial Institutions Improve Their Data Intelligence?

You could write a book on this. Quite a few people have already, but your ability to make improvements boils down to two fundamentals: data integrity and distribution.

How To Repair Data Integrity

Data integrity starts with proper aggregation, and proper aggregation starts with strategic mapping. You may have 25+ potential data feeds (vendor applications, core database, website, marketing tools, CRM, etc.) with 20,000+ measurable items across those feeds. You’re not going to get it all right at first ingestion, nor should you try to wrap your arms around everything on the first day.

Here’s how to get your feet wet:

- Start by (literally) drawing all your systems out on paper or on a whiteboard.

- Identify the top three assets in each system you believe will address your goals (e.g. increased products/household, increased credit card engagement, bill pay adoption).

- Identify the “glue” asset, or assets, between key systems. Customer numbers, Social Security or ITIN numbers, card numbers, IP addresses, and email addresses are common glues.

- Identify the data or file language produced from each system (C, Java, image, text, SQL, etc.).

- Determine if data is convertible to a standard. If not, write clear rules for how the non-standard data will be connected back to the record.

- Ingest a few elements at a time and test the “full view” of the customer record.

- Show a full warehouse record for one customer and then check it against the individual data sources to measure quality.

That’s seven steps. Sounds pretty easy, right? You’ll encounter a lot of incompatibility and system limitations along the way, but the best advice for data integrity is to record everything—every rule, every qualifier, assumption, and missing piece. Keep it all clearly defined against the database solution you use.

Distribute Data and Intelligence Wisely

Banking (like many other industries) has long struggled to find the best way to share good information with their frontline employees and decision makers. There are endless reporting solutions with fancy dashboards and automated or customizable reports. Many offer employees a better view of their customers and prospects than they would otherwise have. However, some key underlying activities can make or break your data distribution strategy as well as the resulting adoption of these types of solutions within your company.

Passive vs. Active Distribution

When do you push information and when do you let users discover it? Think about the timing of each report relative to your employees’ schedules. Is a morning email about prospects the best idea because you’ve trained employees to follow up with prospects during the first 15 minutes of the day? Or is it the worst time for a prospect report because your branch employees are busy returning emails and voicemails, all while scurrying around to get their branches open on time? Ask your employees about timing.

Making It Actionable

You hear this often, but data is only as good as it is actionable. But, for some reason, we fail to provide clear actions within the context of the available data. Since five employees could look at the same data set differently, how do you help guide each of their perspectives? Every report should contain at least three to five scenario-based examples of what to do. Scripts and ancillary training materials help as well.

Onboarding and Training

Training applies to every new process and tool at your company. But, within the financial industry, training on customer analysis can feel like the most unnatural educational topic on an agenda.

Make sure you can track employee engagement with your data reporting tools. You’ll have superusers, monthly users, and inactive users. Many of the inactive users need help understanding the value of the report and how to use it, while monthly users might only engage with reports actively pushed their way. Superusers can be your evangelists and assist your Training department. Understand who falls into which group, then target your training accordingly.

We have a saying at Mabus Agency: “If it’s hard to do, it will never get done.”

We call it the rule of wheNEVER. And if I’m honest, I’m not the first person to discover this phenomenon. A lot of people just call it human nature.

We named this phenomenon as a way to remind ourselves to make things as easy as possible for the end user when developing a new marketing strategy or materials.

We preach the importance of updating a website, developing new content, maintaining brand standards, and promoting campaigns across platforms, but if we don’t give the client the right tools, advice, plan and accountability, their marketing will never get done.

The rule of wheNEVER applies to almost anything in life, but we talk about it most often with websites because websites are living, breathing marketing platforms that often sit on the shelf next to our bikes and hiking packs.

It’s easy to think no one notices when you update your company site, but Google notices. What is even scarier, Google notices even more when you don’t.

If I search for a tree service, and there are two tree services in my area, one that has posted three new pieces of information containing the words “tree service” or “stump removal” in the last three months and one that hasn’t updated since it launched a year earlier, Google is going to provide me with the more relevant result.

We build great, easy-to-use websites, but that’s usually the second biggest reason anyone hires us. The number one reason people hire us is their own inability to write code. Knowing that, we have to develop a dashboard that allows the customer to edit the website without having to learn code.

It would be pretty cruel to tell a customer their website’s success depends on their ability to keep it updated and then hand them a big pile of code.

But here’s the thing, even if we do give someone a website they can easily edit and update, a lot of times the content stays the same for months on end. Why is that? Technical advancements don’t mean a whole lot if you don’t have time to learn or use them.

I’m a writer, and my website goes through some pretty embarrassing dry spells. Why should I expect a carpenter or mechanic to write for his website every day? It’s out of the way. It’s not a part of the normal routine. Most of the time, it’s not very fun.

Here are some tricks we’ve found for getting the hard things done, especially when it comes to your website.

Set a deadline.

Projects without deadlines almost never get done. Projects with arbitrary deadlines have a slightly higher completion rate, but once those arbitrary deadlines gain momentum, they are more often expected by your following and a lot easier to hit each month or week.

Set reasonable expectations.

I had some friends set a goal to blog every day. They were writers who used their blog to practice, but were also busy and only posted something once or twice a month before. The idea was ambitious and after a few weeks, they stopped posting altogether.

Here is why. They set a goal, but the expectation was too ambitious. Failure was guaranteed from the start. If you aren’t adding new content to your website right now, don’t start adding content every day. Set a goal of once a month. That’s easy because you only have to add twelve things in a year. If once a month is too easy, go for every other week.

This includes your promotional and social efforts as well. If you’re doing no promotions, figure out what you can take on consistently. Don’t promote a new Twitter handle just to get tired and quit using it.

Just like with everything else in business grow sustainably.

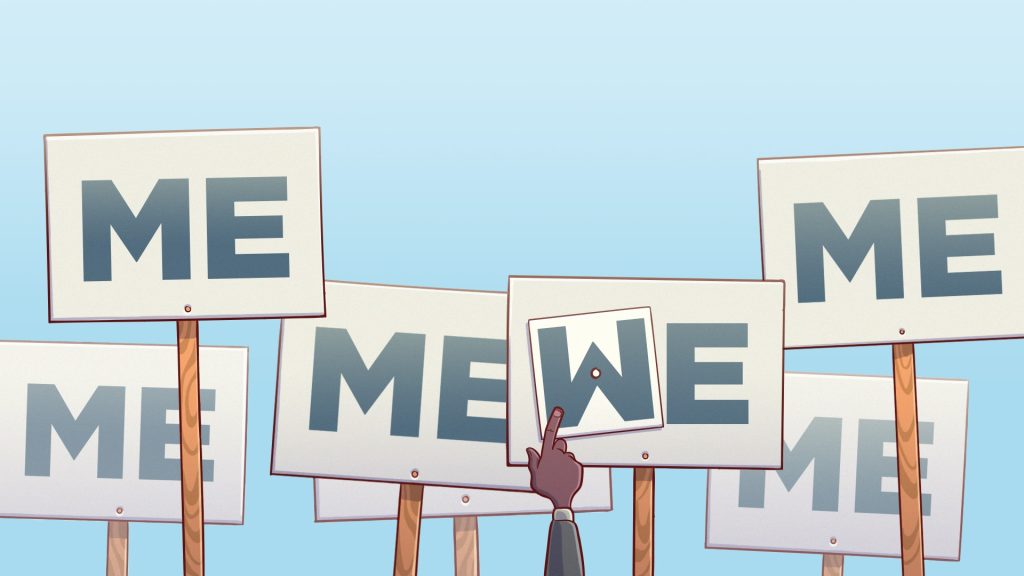

Make it a team effort.

Loop others into your content generation for inspiration and accountability.

It gets even easier when you ask someone else at the company to take two posts and Jerry in finance to take a third. If you have twelve slightly competent content generators in your office, you can each produce one thing a year and have a website that is consistently updating.

Connect with the team members who are already working toward your project goals and piggyback off each other’s ideas.

The secret to making it easy: don’t make it hard.

More often than not, our clients tell us they have nothing to write about. That’s ok, you don’t have to write a giant essay on your profession; you just need to keep adding relevant, searchable words to your website, and hopefully help or entertain someone in the process. If you step back from your blank page and blinking cursor, it’s easy to find relevant content.

Do you have an employee who just passed a certification test? There’s a great post, and it will lead to another post about how important education in your industry is. That post will lead to another about how many talented folks you work with (and a humble brag about all your certifications).

Maybe you had an office Christmas party and just want to share a photo with a good caption. Your content can be 100 words or 1,000 words. It can be a photo or a video. It can be a link to something else you like.

One of the biggest helpers is a big calendar hanging next to your desk. Remind yourself.

Almost everything in life is hard, so when it comes to keeping your website fresh and up to date, make it easy on yourself.

Just know that “When? Tomorrow.” is better than “When? Never.”

I’ve seen a lot of large media companies and corporations whining about ad blockers lately. As a marketer, I’m expected to be the anti-ad blocker — the guy who creates a new scheme to overcome the technological defenses that protect our eyes from the incursion of epilepsy-inducing ads.

The truth is, I have to disable my own ad blocker to read a Wired story just like everyone else.

I use Wired as an example because they got out front of ad blocking earlier this year, publishing the number of their readers who block their ads (20 percent at the time) and explaining how they pay for content. Wired told users they would have to either pay for the content themselves (and offered a very minimal weekly fee for an ad-free experience) or stop restricting ads when viewing Wired content. Now Wired visitors can’t view content until their ad blocker is disabled, which feels like a very reasonable (free) paywall to me.

Ad blockers claim to streamline your web experience. They stop clunky ads from loading and help maintain distraction-free browsing. They restrict inappropriate or harmful ads, and they keep pesky trackers from selling your browsing habits to third parties.

At least that’s the story ad blockers are telling us.

Ad blockers aren’t evil — they’re just telling a better story than the ads they’re blocking, and it’s making advertisers sweat.

Wired ran the first banner ad 22 years ago, and now they’re embracing a model that often means getting rid of their own invention.

Many advertisers, scorned by ad blockers, are running to social platforms like Facebook and Snapchat where ads can’t be blocked. This reckless refusal to listen to the consumer will undoubtedly lead to the new platforms adopting blockers of their own. Facebook is already cracking down on how advertisers use Facebook in an effort to preserve the clear story a user’s timeline tells them.

The two types of prominent ad blockers on the market speak clearly to the issues consumers have with online advertising. The first category is the nonprofit blocker that restricts anything the user hasn’t agreed to view and is especially vigilant against trackers (the technology that show you athletic clothing ads after you visit Nike’s website).

The second type of ad blocker is a business that offers a paid service promising to block ads on pages that have heinous ads, poorly placed ads or an overall abundance of ads. Some of these businesses work with advertisers to find a happy medium — a pleasant online advertising experience.

Honestly, with an ad blocker, I still see some great paid content. Adblock Plus gives permission to advertisements that meet certain guidelines, like placement and size. I think of the company like a consumer-supported Federal Communications Commission (FCC) — listening to the outrage of the consumer and developing a solution everyone can agree on.

And what is the reaction to these rare ads that make it through an ad blocking software?

Users don’t react with anger but are instead happy to see a respectful ad.

In fact, the ad blocking users, who are said to be tech savvy, young and attractive to advertisers, are very attentive and responsive when the ads display at a low volume and with some amount of relevance to their lives.

Before we go much further, there’s a question we should ask ourselves: “Why do we accept it as ‘natural’ that someone would want to skip an ad?”

The reasoning partially lies in the fact that we now know we’re being advertised to and that affects our desire for free will. We view ads as an interruption when we used to view them as informative. Gone are the days where we’re excited to learn about a new product.

At the root of this change is the degeneration of ads. We listened to “the message is the medium” too much.

“If I’m on TV, I’m good!”

There were advertisers who didn’t consider the fact they were running poor quality, locally produced ads as a detriment. They were on TV!

“If I’m on TV, I’m good!” became “If I’m on the Internet, I’m good!”

Then it was all about getting attention. Animated ads flashed “lower your interest rate” and “lose weight now!” If you could shoot the alien, you’d get a free sample!

Medium and technique surpassed strategy, and storytelling, and consumers rejected the bad ads — just as they have on TV and every medium before.

Old Spice got ahead of the game in 2010 by making commercials so funny that consumers went straight to their website with the express purpose of watching advertising.

Geico recently produced a series of hilarious pre-roll commercials that tell consumers they scripted an ad so short they had to keep the camera running in order to fill the minimum ad buy. They made their attempts at advertising the butt of the joke. You can’t skip their ads because they’re already over.

On a more serious note, Dodge’s 2013 God Made a Farmer ad struck such a chord that 20 million people were compelled to seek out the ad to watch it again (and again).

Budweiser’s anti-drunk-driving ad hasn’t seen quite as many views yet but tugs a similar heartstring by using a sweet dog to urge young, single adults to drink responsibly.

These are ad campaigns that are sought out.

They are the Holy Grail of advertising.

They also share something in common: sound strategy and strong storytelling.

Ad blockers aren’t going to ruin online advertising, but poor storytelling will. We can’t continue to throw money at bad storytelling and hope consumers will respond positively.

Each time you publish irrelevant, obnoxious or tone deaf content, you are giving up an amount of the customer’s trust — not only for your brand but for the platform in which you publish.

How can you make a customer’s life better? Geico points directly to the fact they are making the shortest commercials they can. Old Spice is trying to make the consumer laugh. Dodge is playing on the sentimentality of the American spirit. Budweiser is offering a public service through love for our pets.

Ad blockers are what we deserve for placing thousands of obnoxious flashing ads for the last two decades. I’m surprised ad blockers weren’t more common 10 years ago when every ad congratulated me on being the 1,000,000th visitor and offered me a cash prize.

We discovered flashing text, animation, spyware and the thousands of other possibilities and acted like children in an unsupervised candy shop.

Now that the consumer has recovered control of their online experience, it’s our job to win back their trust with better storytelling. It’s our job to place appropriate ads in appropriate places and treat online advertising with the same respect we’ve treated print.

If we want consumers to less aggressively oppose advertising and be less suspicious of our motives, we must offer them an actual benefit and stop begging for their time and attention.

We must earn it.

Imagine for a moment you’re on the cake mix aisle at a grocery store. There are probably 100 different cake brands and flavors that will instantly make you a qualified baker. What does each box have in common?

Most boxed cake mixes require a couple of eggs and some milk or oil to bake a successful, tasty cake.

Believe it or not, there was a time when those boxes required nothing but a cup of water to accomplish such a magical culinary feat.

From 1947 until 1953, the sales of boxed cake mixes that included powdered eggs boomed — all the while the companies producing them debated whether the powdered egg was the best route. They were worried powdered eggs led to an inferior end product, but they feared requiring the addition of fresh eggs removed any claim of convenience.

Cake mix sales slowed during the late 1950s. General Mills hired psychologist Ernest Dichter to interview women to determine the sales drop. Dr. Dichter’s study found that ladies felt using a simple cake mix was too easy — there wasn’t enough work involved, leaving them feeling guilty instead of proud of the cake they made.

Cake mix companies decided adding an egg would end their debate over quality while giving the women of the 1950s and 1960s a better interaction with their product. By requiring a little extra work from the purchaser, they were giving the customer permission to call themselves a baker, increasing the quality of their product and making the result something to be proud about, not ashamed of.

Pillsbury advertisements depicted the box, a bowl and some eggs with the headline, “After this, you’re on your own,” which told the customer they were still doing the hard work of baking a cake.

With the original, all-inclusive cake mix, companies were selling a convenient product. As with most convenience-based products, it had a decent run, but it also had a short shelf life.

When the companies took the time to listen to the customers, they began selling a convenient experience. Not only were these new mixes more involved, but they produced a superior product to their powdered-egg predecessors — a difference undoubtedly noticed not only by the baker but by the people eating the cake as well. The new mix achieved all of this while remaining convenient.

Not long after the addition of fresh eggs, cake decoration became the new metric by which cakes were judged. Now, the homemade cake was simply the canvas and homemakers of the 1960s considered the act of cake decorating a rewarding experience.

This gave cake mix companies another opportunity to create pleasant experiences through frosting mixes. Betty Crocker and Pillsbury weren’t frosting companies, but this new line of “homemade frostings” were value-add products for their flagship cake mixes.

If you read my column regularly, you’ve probably noticed I talk about brand experiences often, and I can’t talk about it enough.

We often overlook the experience associated with our own brand and wonder why brands like Yeti or Under Armor or the fancy boutique up the street do so well.

Most brands with overwhelming success are aware of the experience associated with their products and, in turn, continually tailor their experience to better fit their customer base.

Often, like with cake mix, tailored customer experiences can seem counter-intuitive at first.

The online transportation company Uber offers a more recent example of tailored customer experiences. The company began allowing its drivers to rate its passengers, as opposed to the traditional model, where only service providers receive ratings. Many said the practice was insane or discriminatory. With the gift of hindsight, we can see the rating practice has done nothing but ensure the company maintains its quality level of service by having only the best drivers and customers.

By weeding out problematic customers — or at the least letting the customer base know they are being rated — drivers are happier and the customers who appreciate the service are receiving increased access.

What memories come to mind when you read the words, “brand experience?” Maybe you visited a great shop on vacation one summer, and you’re excited to visit each time you’re back in that city. Maybe you waited 45 minutes for some food that didn’t taste fresh, and now you’re skeptical about giving the restaurant a second chance.

What experience does your brand offer customers?

Are you more personable than your competitors? Are you more convenient, but at the cost of using powdered eggs?

Even if you think you don’t have a brand experience, you do — it just may not be what you want it to be. Talk to your customers. Talk to customers you wish you had. Find out what experience you offer. If it’s good, lean into it. If your experience isn’t what you think it should be, look internally and find a way to change it.

Maybe it’s time for your brand to make the jump to fresh eggs.

Do you ever wonder why the tire company known best for its mascot — a big man made of white tires — is also the most trusted name in fine dining and classical-French restaurant reviews.

Maybe you thought the tire company and restaurant review publication just happened to share the name, Michelin. Actually, one created the other. The Michelin Guide as it exists now, 100 years after its inception, is the result of a marketing campaign going so perfectly it became sentient.

For those unfamiliar with the Michelin guide, it’s a series of annual guide books that awards ratings and reviews to restaurants and tourist destinations. The guide is best known for its Michelin Stars, which are given to restaurants and have been known to affect the success of a fine-dining establishment. One star means a restaurant is very good in its category, two means it is well worth a detour and a third star means the food itself is worth a road trip.

That third star spells out the genius of the Michelin Guide. This tire company was promoting great food in France in the early 1900s when cars were very uncommon, but more than anything it was promoting car travel. At the very heart of it, this high-end restaurant guide was promoting the use of tires.

Think about how genius that marketing plan is. A tire promoted the idea of traveling for food so well that people looked to it for food recommendations, and also tried to get them to the restaurants.

Michelin did what many marketers forget to do: they got around their consumers’ defenses.

That’s one of, if not the biggest obstacle in marketing — getting around people’s defenses.

We see hundreds of brand messages every day at the very least (though some estimates say thousands). No matter how sincere the message or how much we think consumers care about our brand, as marketers we are ultimately trying to sell something.

As consumers, we become rather adept at blocking these brand messages out, whether mentally or by using handy new tools like DVR, online ad-blockers and MP3 playlists.

Marketers try to use humor, entertainment and useful information to circumvent our new built-in ad-blockers. But more often than not, they end up further alienating their brand message, or delivering a punch line that has nothing to do with the brand message.

Michelin got around our defenses by producing something of great value and still remaining dead on target with brand strategy. They tell people about great restaurants and places to travel. They are advertising travel — something the general public perceives as good and even fun — in a way that sells tires.

Keep in mind; this is a time before the Internet or Food Network. You might have not known what’s happening in the next city — much less 50 miles or more away. Michelin provided real value to potential customers while keeping their mission in mind: sell more tires.

It’s easy to approach marketing through a standard advertising mix: print ads, television, radio, etc. The problem is that everyone else can do the same thing. It’s worth spending just a little extra brainpower and preparation to circumvent the defenses of the customer, and we can do it in a way that they will gladly welcome. You do this by providing something of value.

Michelin dedicated its brand image to finding the highest quality of food and restaurants in France — and eventually the entire world. Interested foodies responded by traveling far and buying new tires.

Lowe’s has used its social media brand to show people quick and easy tips for completing projects and maintaining their homes instead of spending all their energy on advertising products. Customers respond by purchasing their project supplies at Lowe’s.

I’ve found a lot of marketers believe consumers care about their brand simply because it exists. That’s not true. Operate under the assumption that no one cares or thinks about your brand, and find a way to make it valuable. Making your brand a value-add keeps you top of mind.

Imagine it: your company puts out a magazine that everyone in the industry uses to stay up to date on industry trends. You don’t even have to advertise because your brand is plastered all over the publication. The moment a customer, competitor or industry peer engages your publication, you’ve just gotten past their defenses.

We have to think like the Michelin brothers did more than 100 years ago.

What value-add can we give our customers?

What niche can our brand fill?

What can we make that is worth driving toward?

You’re unique — just like everyone else.

I’m sure you’ve heard this saying.

Why does it bother us so much when we all know it to be true?

The idea that we’re only as unique as the next person gets under our skin because our very human nature is searching for a unique experience.

Why do you think you get so excited when you take a picture with a celebrity?

It doesn’t happen every day. It’s a unique experience.

You get excited because individual identity is a crucial part of the human experience, and this desire is especially realized in our experiences. You’ve just created a story that is uniquely yours, and one of our greatest desires is to share our unique story.

Sometimes our desire for unique experiences is selfish. Sometimes it’s to help others. Either way it’s innately human.

A friend of mine often tells a story about sharing a bottle of whiskey with a certain “Spiderman” actress while sitting next to a certain author’s grave in Oxford, Mississippi. While this story isn’t interesting to me any longer (I’ve heard it more times that I can count), the first telling is interesting because of the pieces that came together to create one unique night — a night almost no one else can replicate.

NASCAR detractors often argue we only attend races with the hope of seeing a wreck, and while that may be true in part, the deeper drive is to experience something different from anyone before us. After all, no two wrecks are alike.

The same goes for hockey games and fights.

Finding unique experiences drives us to try new things, even if those things are out of our comfort zone.

Herein lies the answer to attracting new customers.

One of my employees (we’ll call him Staniel to save his pride) ran out of gas in the middle of Tupelo’s busiest road during his lunch break this week. When Staniel looked to his left he saw a guy motioning for him to roll down his window. The guy helped Staniel get his truck off the road and then filled it up with the gas can he happened to keep in the bed of his truck.

“Thanks for going out of your way to help me out,” Staniel said.

“Man, I run the garage over at [a local auto dealership]. This is nothing for me. I do it all day,” the guy replied.

You can bet Staniel is going to mention that dealership the next time someone is looking for a new car or needs their car serviced.

Why? Because he had a wholly unique experience — and a great one at that.

Don’t worry, you don’t have to carry a gas can and push other people’s trucks to create a unique experience. That’s the beauty of making something unique; it’s wholly different and wholly yours.

As marketers, we are constantly trying to find a company’s key benefit or unique selling proposition. This is the thing a business does best, and/or the thing customers most need from a business. The problem with key benefits in 2016 is that uniqueness is as hard to find in our business as it is in our personal life.

The Firestone by my office has great staff, service and tires, but so does the competitor down the street. The Firestone gets my business because of their unique location (closest to my front door).

Even with their dedicated and diverse adherents, Apple and Android produce fairly similar products at the basest level.

The product itself is almost moot. We’re buying the associated, unique experience.

You buy an iPhone because of the attention to user-interaction or an Android because you want an unguided experience.

Whatever options you have, you choose the experience that you feel makes you most uniquely you.

There’s some magic in this, though. This notion also creates the highest hurdle we ever ask our client to jump with us: while you might love to do business with every customer, not every customer will love you.

As business owners, we must identify our key benefit. We must also determine our target audience — those to whom the benefit will be most relevant. Then we find a way to build a unique experience for those folks.

Some friends of mine make a really great pair of jeans and they sell them at a price that reflects the quality. People buy the jeans because they’re great, but people can buy great, expensive jeans anywhere. When you buy jeans from Blue Delta, they measure you, they design the jeans with you, and they keep in touch with you after the jeans are shipped.

When I see the Blue Delta tag on someone’s jeans, I already know those jeans have a unique story — a story the wearer is always excited to tell.

They made the experience their key benefit.

What part of your business makes the consumer feel unique? What part of your experience are people talking about?